- Home

- Strutin, Michel;

Judging Noa Page 3

Judging Noa Read online

Page 3

Their howling sounded far away. A strange quiet enfolded him. Now, today, he would die. It was so unexpected. His daughters. His beloved daughters. How could he tell Ada? The bracelet he had meant to give her. Where was it where was it where was . . .

He tasted blood, thick and salty, running into his mouth. His split and bleeding head exploded with pain as the staff caught him again, above the ear, red running in bloody streaks down his face. Zelophechad sobbed, gasping. Then he was still.

“UNCLE BOAZ SAYS maybe you will marry Gaddi’s son. If you do, will he teach me to throw spears? I’ll do anything you want if you ask him to teach me,” Tirzah begged, jittering in front of Malah and Noa, who kneeled under the eaves of the tent, grinding barley.

Covered with barley flour, each bent over her grindstone, crushing the grain a few handfuls at a time. They talked, sang, and made up stories to counter the tedious work of grinding grain with a handheld stone. It was Tirzah’s job to pour kernels from a sack into each concave grindstone, then scrape the flour into a pot.

The sides of the tent were rolled up to admit breeze and the day’s fading light. Near the fire pit, Hoglah and Milcah sorted and parched grain for tomorrow’s breakfast porridge, overseen by their mother.

“Tirzah, no one has decided anything,” Malah chided. “I’m sure Uncle Boaz only said that because you were hanging on his arm, pulling and chattering in his ear until you drove him crazy.”

“God is going to turn you into a boy,” Hoglah shouted from within.

“Good.” Tirzah picked up a long tail of tent rope and tied it around her waist with the loose end flapping in front. She waggled her penis-rope into the tent. “Then I’ll pee on you.”

“Mother, make her stop!” Hoglah screamed.

Noa spluttered with laughter.

“Don’t encourage her,” Malah warned.

“Where is father? He was supposed to bring mother home, not us.”

“He’ll come when he comes. My arms are so tired. How much more?”

Tirzah showed them the contents of the flour pot, half-filled with flour.

“A bit more and there’ll be plenty of barley cakes for dinner . . . if no one eats more than her share.” Malah eyed Tirzah. “Would you give me a sip of water so I don’t have to cleanmy hands?”

“ . . . and wipe the sweat from my forehead, please,” added Noa.

“Tirzah do this. Tirzah do that. I am not your slave.” She stamped her foot.

“Would you like to trade places . . .”

“All right, I’m going.” Tirzah danced away just as a man ran up, breathing hard.

“Your father, your father . . .” was all he managed before a coughing fit overcame him.

Sensing troubleand mindless of their flour-covered arms, Malah and Noa ran in separate directions: Malah to fetch Boaz, Noa to fetch water for the man.

When the man recovered, he pulled Boaz into Zelophechad’s side of the tent and told him he had found his brother’s body. When Boaz pressed, the man said he believed Zelophechad had been attacked, implying beasts of the wilderness. Boaz gathered men from their clan and headed toward the rock-walled basin, while the women waited.

When they thought they could wait no longer, the sisters saw Boaz and his men in the distance, carrying something on a rug. Malah and Noa said nothing, but each knew what it was. Boaz saw Malah and nodded toward their father’s side of the tent. She and Noa ran to inform their mother, explaining what little they knew as gently as they could. Her eyes widened and her face collapsed. The three younger girls heard, but looked blank. To have a father in the morning and none by evening . . .

Malah and Noa, who lost both a father and a teacher, wiped their tear-streaked faces with floury hands and arms. Their grieving white masks frightened Tirzah, and she ran for the cloth and tried to wipe their faces clean even as they cried, holding her, making her job difficult.

In the privacy of his quarters, clanswomen washed what was left of Zelophechad and covered him with a white shroud.

“My husband,” Ada said, “set his heart on the land of his fathers. I don’t want him to lie here, alone. No one will be able to honor him here.”

They sympathized, but they buried him nonetheless.

Anger and grief gave Noa a voice.

“Mother, I vow to you, we will carry father’s bones to the land of our ancestors, to the land we have been promised.”

BY THE TIME of Zelophechad’s burial, word of what the Guardians had done had spread throughout the camp. Boaz called a meeting.

“If the Guardians did not hesitate to kill my brother, a peaceful and honorable man, they would not hesitate to kill any of us. If we don’t stop them now, our slavery will simply be transferred from the Egyptians to these . . . these . . .” Boaz spat his contempt.

Boaz met with other judges and leaders. The meetings spread surreptitiously throughout the camp.

Korach the Levite heard, and said to members of the priestly clan, “How would it look if we simply waited, quibbling among ourselves, while others cleanse us of this plague? We, the true leaders of Israel, must lead.”

Korach approached Boaz. The Levites would, Korach said, offer their good name and lead the fight. Seeing the benefit of collective action, Boaz assented.

They did not wait until the end of the mourning period. Led by the Levites, tribal leaders and young men hungry for battle gathered knives, clubs, whatever weapons were at hand and marched on the tents of the Guardians of Truth. At the sight of hundreds of armed men approaching, the leaders of the Guardians abandoned their sacred mission and their followers as fast as it took them to squeeze under the backs of their tents and race for the empty desert.

THEY HAD COVERED their mother with a soft sheepskin and she snored softly in a corner. She slept on the women’s side every night now that her husband slept with his fathers.

Following the week of mourning, they were relieved to return to work, replacing the hole in their lives with familiar busyness. Hoglah and Tirzah tended the flocks, watering them at the end of the day, then driving them into brush enclosures where Boaz’s men guarded the animals from jackals and wolves. Milcah sat at the loom, weaving under the eaves, while Malah and Noa patched tents, sewed clothes, and endlessly prepared food: grinding grain, cooking, milking sheep and goats, draining curds of whey.

After dinner, they teased wool into thread, winding it onto their spindles in an almost continuous motion, their fingers seeing what their eyes could not in the dim light. Before, they chattered about anything. Now they were subdued by death.

One evening, Noa gave vent to her anger. “The Levites did not confront the Guardians until our father’s murder and Boaz forced them to. I say the Princes of Israel were cowards.”

Tirzah sat in the V between Hoglah’s outstretched legs as Hoglah combed out the tangles in her sister’s hair.

“I would chase them down and slit their throats,” Tirzah swore.

“Tirzah,” Noa scolded. “As for Boaz, mother said he will speak with Gaddi ben Susi tomorrow, to make Malah a match with his son Hur.”

“Hur may be more suited for Tirzah than for me. He’s too young, too untested.”

“Spear-thrower—I’ll take him,” Tirzah said, pulling forward so that Hoglah’s comb tore out a handful of hair, causing Tirzah to howl.

The sisters laughed at the thought of Tirzah subjugating Hur. Malah shushed them, nodding to their sleeping mother.

They lapsed into silence, until Noa cleared her throat.

“Remember when we talked about getting our rights when father was gone? Well, now he is gone and if we don’t speak up for what was due him—and us—we will never get a share in the land to come. Not all of us will be lucky. Marriage is not assured. Husbands die. Without inheritance, who knows which of us may become bondswomen, a step above a slave.”

“Remember Abigail?” said Malah. “Her parents indentured her to a family who remained in Egypt. Even when she’s free to leave, how will she find

her family? She will be alone, with nothing and no one.”

“The further we get from father’s good name, the closer we get to servitude. People forget . . . quickly. That’s why mother wants to marry us off fast. Our family fortunes may crumble like dust unless we find a way to hold them through inheritance.”

“How will we get our share of land?” Hoglah asked.

“We’ll go straight to the top,” Malah cut in. “We will talk with Moses.”

“Moses is still on the mountain,” Milcah reminded them.

“Wait,” interrupted Noa. “We must build legitimacy. What are we to Moses? Before we convince Moses and the Judges of Thousands, we must first convince the Judges of Tens. We must climb the ladder of the courts.

“The count is based on the size of the tribe,” Noa continued. “The bigger the tribe, the more land. Manasseh needs us for the count.”

“Well, of course, we know the numbers.” Malah sniffed.

“Do we have to speak?” asked Hoglah nervously.

“Hoglah, all you have to do is stand tall as a date palm,” Noa said, smiling affectionately, remembering how awkward she, too, felt when every part of her body seemed to grow at a different rate.

“I’m like Hoglah,” said Milcah. “I want to honor father, but I could not speak before judges.”

“I could. You two,” Tirzah pointed her spindle at Milcah and Hoglah, “are like beetles that run when they see a shadow.”

“You, Tirzah, probably shouldn’t speak.”

Noa tilted her head thoughtfully and said, as if to herself, “This will take patience and determination. We have a just request. But we are women, and such a request may never have been granted a woman.”

“Noa is right,” said Malah. “This will not be easy. But if the land promised to Israel is a land of milk and honey, having land in our father’s name will be even sweeter.”

“Noa must be our leader in the law,” said Hoglah.

“I am happy to take on the legal arguments, but Malah must be the battle leader,” Noa said deferentially. “Malah knows Manasseh. With Uncle Boaz’s help, she will get us to the Judges of Tens.”

“What will our jobs be?” Hoglah asked.

Noa looked at them. “Milcah, you can still run in and out of tents. Once our path is known, you can tell us what people are saying.”

“What can I do?” repeated Hoglah.

“You can test the waterskin to make sure it will not leak.” Noa poked at an imaginary skin. “Look for the holes in my argument before I stand in front of the judges. This will be a battle of wits.”

Hoglah grinned, pleased to be elevated to the level of her older sisters.

“Will you promise I won’t need to speak before the judges,” insisted Milcah.

“That is not a vow I can make, but here is one we all must make. For land in our father’s name, each of us must play a part. Who will vow?” Noa challenged.

They all vowed, not knowing how far and where their commitment might take them.

Tirzah broke the solemnity. “If this is a battle, we need a war song.”

“Fine. Your job, Tirzah, is to make the military side dishes to this legal feast.”

“Side dish? My part will be the roasted meat in the middle of the platter!”

CHAPTER 4

SOFTLY IN THE SHEEPFOLD

AS THEY WAITED for Moses to come down from the mountain, the season of infernal heat descended upon the Israelites. Each morning, the sun popped up like a yellow eye, searching for life to desiccate with its hot stare.

By mid-afternoon, the only creatures moving on the blistering desert plain were humans and their flocks. Above, vultures soared on plumes of hot air, their eyes bent to earth, looking for carrion. Leopards and gazelles, snakes and scorpions, jirds and gerbils all stayed in the shade, waiting for the hot eye to shut.

Boaz, Ada, and Malah sat under the eaves of Zelophechad’s tent, discussing Malah’s worth and what that meant for negotiating her marriage. In her father’s absence, Malah had insisted on attending, fearing her mother was too accommodating to defend her daughter’s best interests. Ada did not say “no.”

“Our flocks . . . I already know their worth,” Malah said.

“Yes, but not their worth in gold,” Boaz returned. “If you are a family of women, it is better to wear your wealth on your arms than try to protect wealth on the hoof. Of course, I will watch over you, each of you. But gold is simpler to guard.”

Ada nodded in agreement with her brother-in-law.

“Gold might fluctuate in value, but the amount would remain fixed,” Malah said, using the argument Noa had devised. “It will not increase. From what our father taught us, we can increase our flocks. And, so, our wealth.”

Her mother, hearing this new argument, nodded in agreement, this time with Malah.

“So, my brother taught you to be a breeder of goats. And sheep.” Boaz laughed. “He did not think getting a husband was good enough?”

“What does one have to do with the other? And why should we not control what is ours?”

Ada cringed at Malah’s tone.

“‘Control.’ ‘Yours.’ These are strong words for a maiden.” Boaz smiled, amused by her indignation.

“Noa’s words,” Malah said, thinking she had gone too far.

Earlier, when Malah and Noa had learned of this meeting, Noa cautioned Malah that Boaz would not understand their need to protect what was theirs, especially since Seglit, Boaz’s wife, was proud of her worn wealth. They knew little about Seglit beyond her fine-boned, feline beauty. Everyone attributed Seglit’s aloofness to the fact that she could not bear children.

When Noa was coaching Malah on how to retain a share of the livestock, Malah said, “Boaz is even tempered and considerate. Why would he marry such a woman?”

“Maybe because she tops his even temper with a hot temper . . . at night.”

“Noa. He’s our uncle.”

“I hear that uncles have all the same parts as other men.” Noa laughed.

Malah laughed, too, but seemed unsettled.

At their meeting under the eaves, Malah tried to bury the image Noa thought so hilarious, but her itchiness remained.

Without thinking, she challenged him. “Come with me after my sisters bring in our flocks . . . before you trade our sheep and goats for gold on our arms.”

Later, Malah and Boaz cast long shadows as they crossed the broad oval shaped by the ring of tents. Headed toward the brush shelters beyond, they passed the clan’s few camels, hobbled for the night, kneeling on the desert floor chewing their cuds. Tethered asses stood still, lulled by dusk, occasionally shifting their weight from one leg to the other.

They left the ring of tents, and Malah pulled her robe more tightly against the cold, arid night air. Boaz nodded at the guard posted at the brush shelters. Lounging on a mat, the guard lifted his head in a gesture of recognition, then returned to the gaming bones he threw down as solitary amusement until it was too dark to see.

Rutting season had not yet begun, but hormones were on the rise. Rams and he-goats, feeling a surge in the pulse of life, paced back and forth at their stakes, eyeing rivals. Females and young stood in close groups, occasionally revolving as one, like a half-sleeping dog circling to find a better position.

As they passed the pens, waves of heat rose from the livestock accompanied by the pungent odor of goats, oily fleece, and sour milk.

From the pen that held the sisters’ animals Malah and Boaz heard the soft bleats of sheep and the “Beh-eh-eh-eh” of a he-goat. A ram and a he-goat were tethered each in a corner, the tip of the goat’s left horn cracked from a faceoff with a rival. The several dozen sheep and goats in the pen were a mix of females and the immature of both sexes. Malah picked up the long shepherd’s staff that rested against the open-weave branches of the pen, looked back to see that Boaz was watching, then reached over to tap one of the larger sheep.

“You see this one?” She ran the staff along

the back of the ewe. “She produces the softest, most pliable wool.”

“So, you’ve found a good sheep.”

“No, we didn’t find her. Her line does not lamb well, but we’ve bred them with those that do.”

She rested the staff against the pen, untied the rope that held the gate shut, and squeezed inside.

“Would you hold the gate to for a moment?”

She shuffled around in the pen, feeling one lamb, checking the ear of another, until she found the one she wanted and lifted it up. She tucked the first lamb under one arm, stooped down and wrapped her free arm around another, and struggled to her feet with the bleating burdens. Then she carried them, one under each arm, back to the gate. Boaz opened the gate just enough to let her out.

“Here, feel the wool of this lamb.”

“Very soft.”

“Now feel the wool of the other.”

The wool of the second lamb was far softer and finer than any of his.

“How did you do this?”

“Father’s instruction, trying, and luck. And, of course, God’s help,” she offered, not wanting to appear as proud as she felt. “Midianite traders come looking for the wool of our sheep, willing to pay a high price. The word goes out, and others learn of our wool.”

“Your father spoke of your success, but I thought he was just a proud father. I confess, I paid little attention.” He was silent a moment. “So now you are wondering why your inconsiderate unclewants to deprive you and your sisters of something of increasing value for gold that will sit on your arms and necks but earn nothing more?”

She smiled broadly, then cast down her eyes. But she could not suppress her delight in Boaz’s recognition of her accomplishments.

“You know, it’s not just the wool. We’ve also been breeding for richer milk. Before our sheep’s milk goes off for the season, you should try some, fresh. And the cheese we make . . .”

She licked her lips to emphasize its goodness.

“I have eaten this fine cheese in your father’s tent.” Boaz laughed, but his eyes fastened on her moist lips. He noticed her arms and hands, wrapped around the lambs. Big hands with strong fingers. He looked back at her face, her eyes luminous in the failing light.

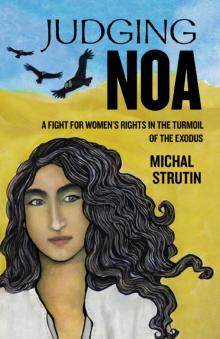

Judging Noa

Judging Noa